- Home

- Stacey Madden

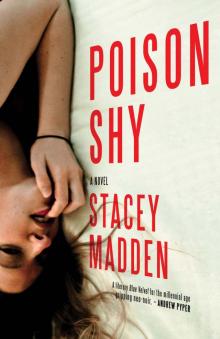

Poison Shy

Poison Shy Read online

POISON

SHY

STACEY

MADDEN

ECW PRESS

To the memory of Robert Brown

0

My worst fear? Insanity. All the different kinds of crazy.

Paranoid, psychotic, deranged.

Homicidal.

It’s not so much being insane that scares me as the prolonged descent, degree by fractured degree, into the cavern of madness. Not the oblivious haze of the landing place but the horror of the journey. The creeping awareness of your own mental disintegration.

My name is Brandon Galloway. I don’t have a middle name. I grew up in a place called Frayne, a blue-collar nowheresville in southwestern Ontario. Aside from being an open sanctuary for addicts, drunks, and aging prostitutes, it’s also a college town — home to Frayne University, which the students devotedly refer to as F.U.

A vine-wrapped, yellow-stone behemoth that looks like a giant birdhouse with tentacles, F.U. is a place for students with average grades and parents who can’t afford to send them elsewhere. Some say it’s the pride of the town, a symbol of respectability. I say it’s a red herring: nothing but a small-town sham.

When the university was founded in 1964, it split Frayne into two halves: right and wrong. The red-brick and white-picket-fence homes on the residential east side comfort the teachers, aldermen, and small business owners, while the rubbled tenements of the west shelter the steel worker and janitor types, along with the unemployed, the forgotten, and the ignored. The dividing line is a long bustling road called Dormant Street, the aptly named downtown core, where the students lie oblivious to the simmering poverty of the west and the taken-for-granted entitlement of the east, until life sees fit to kick or hoist them in either direction. Or until they leave town, like I did.

These days, whenever someone learns I’m a Fraynian by birth, I can almost hear their thoughts. They wonder if I was involved in the kidnapping of Melanie Blaxley or the murder of Darcy Sands. It was the only time my hometown made the national news.

I tell them I wasn’t involved. But I was.

I didn’t have the happiest childhood, but I was an adaptable kid. Mostly I was invisible, hovering in the background of my parents’ smash-up derby marriage, a mere afterthought in their battle of emotional attrition.

My father worked as an electrical technician. He moved in and out of our home more times than I can remember. He was the kind of man who could fuck a waitress at a motel in the afternoon, then snore in my mother’s bed at night with an undisturbed conscience. On his forty-first birthday he suffered a heart attack in a strip club bathroom and died. He wasn’t living with us at the time.

My mother started showing signs of schizophrenia in her mid-twenties, and was finally diagnosed after Dad’s death. His philandering didn’t help. My mother was prone to bouts of violent jealousy. Somehow I always knew she was crazy, even before I knew what crazy was, though it didn’t affect my love for her. It’s common to love and fear something at the same time. Religious fanaticism is a prime example of this phenomenon, and my mother was one of those, too — a fanatic, that is. Schizophrenics cling to religion because they believe everything on earth is out to get them, and in many ways they’re right. The world is hostile and everything in it clashes. My mother and father were about as suitable for each other as a nun and a gangster. It often made me question the legitimacy of my existence.

At school I sat at the back of the classroom, blending into the coat rack with an ashen complexion and earth-tone clothing. I was the student the teachers always had trouble remembering, a receiver of mediocre but unworrying grades. I once achieved a 72% in a class I’d stopped attending months before the end of term. “A valiant effort” was what the teacher wrote on my report card.

I wasn’t picked on because the bullies didn’t know who I was. I won the “participant” ribbon at the school track meet, finished eighth runner-up at the science fair, and signed out library books with fake names and never got caught. The flying pudding cups and bologna sandwiches of cafeteria food fights always seemed to miss me.

After school I’d go straight home, close my bedroom curtains, and get lost in a video game with the volume turned down. I didn’t want my mother to know I was home; otherwise I’d have to sit through a Bible lesson.

When I grew bored of blowing away zombies, I’d peep out my window and invent life stories for the neighbourhood passersby. My seventh-grade teacher, Mr. Zettler, was a government agent working undercover. Patricia Moreno, my neighbour and classmate, was the descendent of an ancient Mayan emperor with supernatural powers. The garbageman with the eye patch was secretly writing an adventure novel that would one day make him rich. I heaped fame and fortune onto strangers but gave no thought to my own hopes and dreams. I was a comfortable nobody. I spent my youth watching the world and hoped it wouldn’t notice I was a part of it. My primary concern was security, and my means of achieving it were simple. Stay out of sight and out of trouble became my personal motto. I believed I’d found the secret to longevity, and I shared it with nobody.

By the time I finished high school, however, I’d grown tired of being a spectator. I enrolled at F.U. and applied for student housing. I wanted to break out of my solitude and get involved in something social, like the Drama Society or the Athletics Club. It didn’t take me long to discover that all the drama geeks were pretentious assholes, and that most of the vein-pulsing jocks were closet homosexuals who fucked sorority girls for sport and secretly pined for each other in the locker room shower. It wasn’t something I wanted to be a part of.

After another year of average grades, no friends, and a loneliness gloomier than the one I’d felt in high school, I moved out of my dorm and dropped out of school entirely. I spent my days that summer hanging around the public library, reading horror novels in the mornings and scouring the want ads in the afternoons. I worked as a pizza delivery guy, a telemarketer, a grocery bagger, a dog walker, and endured two whole shifts as a clerk at a stationery store before being fired for doing crossword puzzles behind the check-out counter.

Finally, I settled for a dishwashing gig at a bar near campus called The Place. Eventually I worked my way onto the kitchen staff, preparing mayo-thick Caesar salads and brushing suicide sauce on Buffalo wings. I earned minimum wage, plus a small percentage from the collective tip jar and a doggy bag of leftovers at the end of every shift.

Patricia Moreno, my childhood neighbour, was one of the servers. In just a few years she’d transformed from a long-eyelashed pre-teen into a chubby sex-bomb, forever doomed to wax her upper lip. A spicy Latina who could flirt with the customers with her hips alone, she was the only other staffer my age, so we spent a lot of time together. Eventually, almost without my even noticing, we became a couple.

I couldn’t tell you how long we dated. The start and end points of our relationship were too vague and tranquilized to be assigned firm dates. We came together out of convenience, but remained emotionally detached. It was strictly business at work, board games and movie rentals on our mutual days off.

In the beginning we spent a good amount of time in bed, but once we got used to each other’s kinks (she liked to be held down, I liked to do it standing up), we pretty much stopped fucking altogether. She refused to have sex on Sundays (the Lord’s day) or anytime after work (“My feet stink, Brandon. Are you crazy?”), which pretty much left no time at all. Her parents hated me because I couldn’t speak Spanish, or even French. To them I was just another Canadian-born kid with no ambition and hockey on the brain (which was only half-true — I’ve never been much of a sports guy).

She confirmed the break-up I long suspected over the phone. She called from a bu

s station in Montreal, said she’d gone to start a new life. She’d been plotting her escape for months.

I mourned her departure with a basket of chicken fingers and three shots of tequila. What upset me wasn’t that she’d left, but that she’d managed to take a risk and actually do something before I had.

At this point I’d been working at The Place for seven years, the ones I’d been told are supposed to be the best of your life. I lived alone in a small apartment above a twenty-four-hour laundromat, slept on a soggy mattress that folded up inside a couch. On my days off I’d fall asleep with my hand in a bag of Cheetos and a dog-eared Stephen King on my chest, only to be ripped from my slumber by the shaking and buzzing of the dryers downstairs. I had no savings, no hobbies, and no friends to speak of besides an ex-jock from my old high school named Chad Baldelli. He’d been kicked off the football team at McMaster after suffering three concussions in his freshman year. He came into The Place at least three times a week and bored the flies off the walls with his endless musings on what might’ve been, before being helped into a cab at three a.m., drunk as a donkey and weeping into his empty wallet. I felt for the guy. I loaned him my ear a couple of times, and before I could remind him that we’d never actually spoken in high school, he’d latched onto me like a virus.

“Yo, bartender! A brewski for me, and one for my best buddy here!”

More than once he suggested we hit up a strip joint in Toronto, or at least a sleazy nightclub — “Where the girls get drunk and dance with their asses hanging out.”

I’d shirk the topic and bring up Patricia.

“You’re living in the past, dude. Come out with me and I’ll introduce you to some honeys that’ll make you forget all about her.”

Chad quickly became my only friend, not that I ever took him up on his offer to go “snatch hunting.” He brought me out with him once or twice, and invited along a few old flames from his glory days — ex-cheerleaders who were now either waitresses, nannies, or cashiers at the Stop N’ Save — no one interesting enough to lure me into reliving the passionless sitcom of my previous relationship. Even Chad’s antics, which had distracted me for a while, were starting to get old. I needed a change, something to help me figure out who — or what — I was.

Then something remarkable happened. A few weeks after Patricia left, like some divine mercy, The Place was shut down after a rat infestation. I heard the exterminator say it was the worst he’d seen in his twelve years on the job.

Twelve years killing vermin. The thought struck me as poetically macho. Sad and noble at the same time, not to mention secure. It wasn’t like insects or rats were going extinct anytime soon.

I wrote up a resumé and dropped it off. Within the week I was called for an interview. By sheer luck they’d just had three employees leave for higher-paying extermination jobs in Toronto. Despite my lack of experience I was hired on the spot. I was told I had the eyebrows of a bug killer, which I took as a compliment.

I shook the man’s sandpapery hand and waited for him to ferret out a uniform from the maze of boxes in the back room.

1

I first saw Melanie Blaxley the day I fumigated her apartment. I’d been working as a junior exterminator for Kill ’Em All Pest Control for a few solid months. My supervisor was a guy named Bill Barber. He was fortyish, unmarried, overweight — exactly what you’d expect of your neighbourhood bug guy. A friendly blue-collar slob. I was the one who looked out of place.

Melanie was a student, living in a shabby two-bedroom apartment with her roommate, Darcy Sands. Their problem was bedbugs. I remember standing on the sidewalk outside their building, waiting for Darcy to clear out. Melanie was sharing a cigarette with Bill. She was a redhead, pale and freckled, with eyes so icy green they resembled the stick of spearmint gum I’d just popped into my mouth. She wore a low-cut purple top that speared down between her small breasts and a frayed pair of cut-off jean shorts with a bleach stain on the ass. Small, scabby bites ran up her legs from her ankles to her thighs. It was early October and the weather was mild.

She must have caught me staring, because when she finished her cigarette, she flicked it in my direction. It landed inches from my shoe. For some reason I had the urge to bend down and pick it up. I didn’t smoke and never have, but Melanie had left a smooch of lip gloss on the filter and I wanted to know what it tasted like.

Darcy came slouching out of the apartment as I fought the urge to pick up the butt. He had five or six enormous textbooks in his hands. He looked pissed.

“This is not a great time for a fumigation, you know,” he spat. “I have a philosophy paper due and now I’ll have to write it at the goddamn library.”

At the time, I assumed he was talking to Melanie. But thinking back, it’s possible he was talking to me and Bill. Or himself. Or nobody at all.

“You guys got everything you need?” Bill asked them. He attempted to hike up his pants despite his enormous gut. “Once we start you can’t go back in for at least twenty-four hours.”

“Wonderful,” Darcy said. “Looks like I’ll be checking into a cubicle tonight.”

“Hey, we gave you notice —” I said, but Melanie cut me off.

“It’s okay, he knows. He’s just being an asshole.”

I looked directly into her face for the first time. She gave me a crooked smile, which could just as easily have been a smirk of contempt. There was something distinctly feline about her. A subtle predatory glint in those green eyes of hers. The freckles suited her. They seemed to be scattered symmetrically across her face, the same minute distance between each spot with not a single one out of place. She was beautiful in a trashy kind of way. I imagined her as the surprisingly attractive offspring from an incestuous marriage.

“What about you?” I asked her. “Do you have a place to stay?”

She laughed as if she was mocking and forgiving me at the same time. “Yeah, I got it covered.”

I stood and watched her walk down the street with Darcy. She took a few textbooks out of his hands to share the load. He tried to trip her, but she swerved to avoid his foot and whacked him playfully on the shoulder. As they turned the corner, Melanie doubled over laughing at something Darcy had said. It was ridiculous, but I felt they were joking around about me. I also felt there was more to their relationship than just splitting the rent.

But all of this is hindsight. At the time, their closeness bothered me because I was attracted to her, and Darcy was biological competition.

“You coming, Brandon?” my supervisor called from the building’s front steps.

“Yeah, sorry Bill.” I spat my gum onto the curb and followed, the bottles of bug spray on my belt clanking like tin cans.

My mother was still alive at this time.

She was a recluse, shut away in her tiny apartment, only venturing out when the government shot laser beams through her window to intercept her thoughts. She had this disgusting woollen blanket she kept wrapped around herself at all times — when she ate, when she slept, when she went to the bathroom. It was Halloween orange and smelled like it had been pulled out of a dumpster. It was encrusted with food stains, boogers, and God knows what else — she never washed it. For her, it was literally a security blanket, some kind of signal-muffling force field that kept her safe from harm.

Whenever those government lasers came beaming through her windows, usually between three and five a.m., she’d burst into the hall, donning her blanket like a cloak, and begin banging on her neighbours’ doors, cursing like a lunatic. She was the filthy woman with the wild hair, the blanketed zombie in 33C who gave all the kids nightmares.

“Why in the world would the government want access to your thoughts?” I asked her on one of those rare occasions I felt bold enough to challenge her conspiracy theories.

She looked at me and held up a veiny, trembling hand. “If I told you, then you’d be in danger, Brandon.” She

hacked up some phlegm and spat into the bucket at her feet. “They never target the target. They’re very cunning. They go after your loved ones. That’s how they violate your soul.”

I wanted to vomit at the thought of someone I loved being so far gone. I was filling her fridge with groceries at the time, so she didn’t see me shudder. All the teenagers I’d tried to hire as grocery boys had quit. She’d scared them away with volcanic prophecies of doom and death. In the end I had to do the shopping myself, but I didn’t mind. It gave me an excuse to visit, and I think she was grateful for the company.

One time, while I was organizing soup cans by brand — she was meticulous about this for some reason — she said, “I saw the woman drunken with the blood of the saints.”

I turned to look. Her gaze was fixed on the TV screen. She was watching one of those televised religious services on mute. An old man in a purple robe lifted his hands toward the stained glass above his head.

“Are you talking to me, Ma?”

“Hmm?”

“You said something about a drunk woman . . .”

“I did?”

“You just said it, Ma.”

She stared at me blankly. “I must have been talking to Jesus.”

I shook my head, my heart crumbling a little at what she’d become. It’s only now I can see that she was giving me some kind of warning, whether she knew it or not.

A good chunk of my paycheque went to booze. I was twenty-nine and single with a decent job and very few living expenses. My apartment above the laundromat was rent controlled. I ate a lot of fast food: macaroni, veggies and dip, canned soup, peanut butter and jelly — your basic bachelor’s diet.

Chad was my sole drinking buddy. His rediscovered lust for women had helped him forget about his sporting fame that never was. He liked them tall and full-figured, with big asses and saggy bell-clapper breasts. A girl who could touch her nipple to her belly button drove Chad wild. No matter where we went, he always seemed to find a girl who just happened to be into meatheads with out-of-control chest hair.

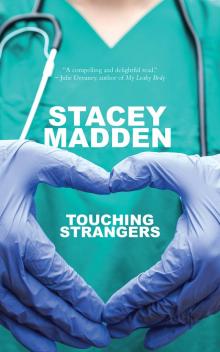

Touching Strangers

Touching Strangers Poison Shy

Poison Shy