- Home

- Stacey Madden

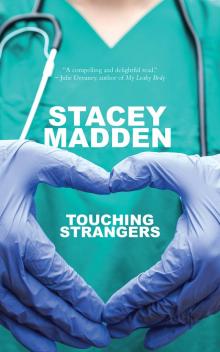

Touching Strangers

Touching Strangers Read online

TOUCHING STRANGERS

“Madden’s writing, like the virus in this novel, is quick to infect thereader. His words get under your skin and worm their way to yourheart and guts.”

~ J. Kent Messum, Arthur Ellis Award winning author of Bait

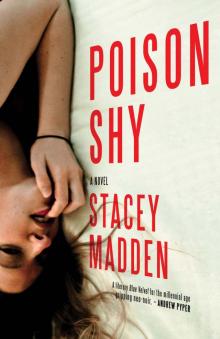

ALSO BY STACEY MADDEN

Poison Shy

TOUCHING STRANGERS

A Novel

STACEY MADDEN

Copyright © 2017 by Stacey Madden

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproducedin any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews.

Publisher’s note:This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places andincidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Madden, Stacey, 1982–, author

Touching strangers / Stacey Madden.

ISBN 978–1–988098–24–1 (softcover)

ISBN 978-1-988098-41-8 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-988098-44-9 (Mobi)

I. Title.

PS8626.A314T68 2017 C813’.6 C2016–907595–8

Printed and bound in Canada on 100%recycled paper.

eBook: tikaebooks.com

Now Or Never Publishing

#313, 1255 Seymour Street

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada V6B 0H1

nonpublishing.com

Fighting Words.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the British Columbia Arts Council for our publishing program.

For X– I’m sorry.

“Only the sick are healthy.”

~Howard Jacobson, The Act of Love

STAGE 1: DEAD BIRDS

He put on a pair of clear plastic disposable gloves and a surgical mask and left his apartment, locking all three bolts on the door. Samantha wanted blueberries but she refused to leave bed. The grocery store, CanPrice, was two and a half blocks, or five-hundred and twenty-seven steps, from their building. It was a Tuesday, 1:08 in the afternoon. Not many people would be out shopping. All Aaron had to do was pick out a container of fresh organic blueberries, join the shortest checkout line and be sure not to touch anyone, and he’d be home before he could say streptococcal pharyngitis. If everything went according to plan, contamination would be minimal—nothing a scalding hot shower couldn’t kill.

It was May. The air smelled of blooming flowers and carexhaust. Aaron stuffed his plastic-covered hands in his pocketsand speed-walked through the side streets, puffing into his mask.

A man in a Hawaiian shirt moved toward him in the distance, a plastic bag flapping at his side. Aaron grunted at the sightof another human being.

As the flowered shirt waddled closer, he could see it wasDoug Chisholm, a man from his building. Doug was a car salesman who could easily afford to own a home, but had made alife choice to live in a small bachelor apartment and spend hismoney vacationing at all-inclusive resorts in the Caribbean. Heaveraged five to six trips a year, and always came back smiling,sunburnt, and with a slightly larger bald spot.Aaron suspectedhe also spent a great a deal of money on prostitutes—anassumption based on Samantha’s window reportage.Theysometimes said that while not cultivating skin cancer on a whitesand beach, Doug spent his time in the city increasing hischances of contracting HIV.

“Howdy!” Doug called, offering Aaron a Boy Scout salute.

Aaron stopped to ensure he was at least eight feet fromDoug. “Hey.”

Doug pointed at his own face and swirled his finger in a circular motion. “What’s with the thing? You sick or something?”

Aaron shrugged and held his breath. He stared at the liverspots on Doug’s shiny head.

Doug just smiled and nodded. “Well, get well soon. There’sa lot of nasty stuff going around. I don’t feel so hot myself.” Heheld up the plastic bag. “Got myself some Robitussin. Lots of sickpeople on the plane. Might have caught something.”

Now that he mentioned it, his complexion did seem a bityellow. His eyes were glassy and bloodshot, and there was somekind of rash on his neck. Aaron began to cross the street.

“Well, see you later!” Doug said.

Aaron felt a tingle in his spine as he continued toward thegrocery store. Further down the street there was a young girlwith a skip rope. At the sight of Aaron she ran onto her porchand stared at him from behind the balustrade. He waved at her ashe passed. This was the kind of reaction he wanted. His objectivewas to be avoided. The mask was a godsend: not only did it prevent him from inhaling other people’s germs, it was an ingeniousblocker of human contact. Ever since the SARS outbreak of 2003, people in Toronto regarded the public donning of surgicalmasks as both a warning and a threat. Stay away from me or else.Since he’d moved in with Samantha, Aaron hadn’t left the apartment without wearing one.

He reached the corner, turned right, and stopped dead.There was something on the ground ahead of him. A lump. Hecrept forward and discovered it was a dead bird, stiff and bent up,right in the middle of the sidewalk, its sparse feathers quiveringin the breeze.

He looked skyward, half-expecting an apocalyptic downpour of avian carcasses, but there was only the smoky grey troposphere, cloudless and empty.

He wondered how long the bird had been there, whetheranyone had moved it or stepped on it. Had it just died mid flight? He thought about bird flu, the ever-evolving, mostwidespread flu virus of them all. He adjusted his mask, then puthis gloved hands in his pockets. He wasn’t close enough to determine what kind of bird it was, but he was pretty sure it was apigeon. How deadly was a dead pigeon? He was angry with himself for not knowing. He and Samantha had recently studied upon swine flu due to a mini outbreak in Toronto, but all the factspertaining to bird-related diseases seemed to have slipped out ofhis head. He hoped it wasn’t early-onset Alzheimer’s.

He paced in a square pattern on the sidewalk, the surgicalmask keeping him from hyperventilating. He remembered therewere three human diseases associated with pigeon droppings:histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, and psittacosis—none of them tooserious. He knew this because he thought he’d contracted psittacosis the time Samantha’s father’s parrot shat on his shoulder.

But that was irrelevant now. The dead pigeon in front ofhim had shat its last shit a long time ago.

He leaned forward and took another look at the corpse: thecrushed head, the tattered gizzard, the cluster of ants crawling allover each other in the eye socket. It was a gag-worthy sight. Ina way he was glad he’d seen it—it gave him a reason to brush upon his knowledge of bird diseases. He made a mental note to tellSamantha about it too. She’d definitely want to know about birdsmysteriously falling out of the sky in their neighbourhood.

There was a sound of shoes on pavement behind him. Heturned around. The girl with the skip rope was standing at thecorner, half-hidden behind a fence. It dawned on him that sheshould be at school. She was probably off sick, infested withschoolyard contagions.

He stumbled and almost tripped over the bird’s remains. Thegirl giggled. He turned away, embarrassed, and saw CanPrice’salmost empty parking lot in the distance.

He clapped his plastic-covered hands together. “Right. Blueberries.”

*

Samantha was sick. Very sick. Probably dying. Aaron wouldcome home with the blueberries and find her corpse in their bed,straw-haired and blue-lipped, locked in rigor mortis.

She’d have died of some unknown super-

disease that wasultra-rare and fatal one-hundred percent of the time, thoughshe’d be the world’s only known victim. It would be sudden andpainful—symptomless until the final excruciating heart thump.Doctors would be baffled. There would be an inconclusiveautopsy. She’d be a case study in medical journals for decades.

She turned her head on the pillow and waited for blackness.

What came instead was the chorus to Space Oddity by DavidBowie, blasting from the stereo of a vehicle in the building’sparking lot.

Bowie sang, “Now it’s time to leave the capsule if—”, andthe engine was killed.

Samantha experienced a miraculous surge of energy at thesound of the car door opening. She crawled across the bed, puther fingertips on the windowsill, and peeked through the curtainslike a curious child.

Hopping out of a mud-brown pickup truck was a youngman, probably around Samantha’s age—twenty-five, twenty-sevenish—in a tight black T-shirt and faded jeans. In one hand heheld a Tim Hortons coffee, in the other a set of keys. He had darkhair with a slight speckling of grey around his temples despite hisotherwise youthful and, dare she think it, rugged appearance. Hissquare jaw was coated with a two-and-a-half day beard—the kindof facial scruff she wished Aaron could grow, the poor blondie.

Samantha had never seen this guy before, which was odd,because she was fairly sure she knew everyone in the building,either by name or face. Could he be a new tenant? There wereplanks of wood and a tool box in the back of his pickup. Maybehe was here on a job. A hired handyman or something.

He sipped his coffee and swung his keys around his fingeras he made his way across the lot. Samantha opened the curtains wider for a better look.The guy was dirty and sweaty.His clothes were dusty and flecked with paint. He probablystank. Samantha imagined he’d have a musky, bug-repellent type smell. She wondered what he’d look and smell like aftera shower.

He fumbled with his keys and used one to let himself into aground-floor unit across the lot—Ms. Fenster’s old apartment,the place where she’d laid dead and rotting for six whole days onher kitchen floor before the superintendent, Mr. Böröcz, caughta whiff of ripe death and let himself in. He’d allegedly renovatedthe place, but Mr. Böröcz wasn’t exactly the picture of hygieneand sanitation. He’d turned the place over in a mere ten days. InSamantha’s opinion, the unit still qualified as a bio-hazard.

Samantha wanted to warn him about the septic enclosurehe’d just walked into, and if she hadn’t been so gravely ill herselfthat’s exactly what she would’ve done.

She stepped out of bed into her googly-eye slippers, shuffledto the bathroom and opened the medicine cabinet. Vial uponvial of pills and ointments lined the shelves, from shortest totallest, each representing a different level of salve or intoxication.She squinted and scanned the bottles, deciding which was best tocombat her current ailment.

The room smelled of disinfectant and prophylactics. On thefloor beside the tub was a massive bottle of rubbing alcohol, thesize of a water jug, on which she and Aaron had installed a spout.A bag of cotton balls hung on the doorknob for easy access. Onthe left ledge of the sink was a motion-sensitive dispenser ofwatermelon-scented hand sanitizer; on the right, a bottle ofantibacterial hand soap, with a pump she sterilized with alcoholafter each use.

The toilet was fit to drink from, not that she or Aaron wouldhave dared. Resting on the lid were two stainless steel boxes, theexact same size and shape: one of them filled with Kleenex, theother with plastic disposable gloves. The whole room was spotless, immaculate. Surfaces sparkled in the white light.

Samantha plucked a thermometer out of the cabinet, stuck itin her mouth and went to the kitchen. Poured herself a tall preventative glass of cranberry juice—she was prone to bladderinfections—and waited for the thermometer to beep so it couldtell her how close to death she was. She sat on a stool, naked except for her googly-eye slippers, and stared at her glass of juice.It looked like a pint of blood.

When the thermometer sounded she plucked it out of hermouth. It read 98.6°.

“Holy Münchausen,” she said. Her voice echoed in thepine-scented silence.

*

CanPrice smelled like rotting vegetables and mop water.

It was no surprise to Aaron. Grocery stores were typicallyrun by one middle-aged alcoholic manager and a squad of aboutfifteen teenage boys with greasy hair and dirty fingernails. Youwere lucky if the only thing your local grocery store smelled likewas rotting vegetables.

He made his way to the display of organic blueberries onsale, looking every shopper he passed in the face with wide-open,panicky eyes so they’d know to keep their distance. He didn’twant to shout “I have a disease!” at anyone who got too close,but he would if he had to.

A pair of seniors on motorized carts were rummagingthrough the blueberry cartons, stacking and re-stacking them insearch of the perfect bunch.

Aaron stood aside and pretended to pick through a pyramidof tomatoes. The elderly woman had a collection of dirty stuffedanimals bursting out of the basket attached to the front of hercart. The old man’s basket was filled with cans of discount brandmushroom soup. Resting on top of the cans was what looked likea half-eaten cheeseburger wrapped in ketchupy tinfoil. Aaroncould hear the fluid in the man’s lungs with each of his cracklyintakes of breath.

“Look here,” the woman said to the man, holding up acarton of berries. “It says, ‘Product of Michigan’.”

“No wonder they’re on sale,” the man growled. “Forget it.”

They rolled away in slow motion, the man behind thewoman, leaving grease prints and invisible pathogens all over theblueberry display. Aaron had a small pack of antibacterial wipes in his backpack for just such an occasion. He stood looking at thedisplay from a distance of two feet. The fact that the berries camefrom Michigan put their organic status in doubt, but Samanthawould be mad if he didn’t come home with something. It wouldbe wise to get one of the cartons from somewhere near thebottom of the heap. He held his breath and stepped forward.Moved four or five boxes out of the way, plucked one atrandom, and immediately started wiping it down as he dashed forthe checkout like an Olympic speedwalker, paying little attentionto his surroundings. He just needed to get out.

A little boy stopped and stood in his way, candy-stainedmouth agape. “Mommy!” he called. “A hospital man!”

The boy’s mother dropped a can of corn and yanked her sonout of Aaron’s path. The boy started crying. People wererubbernecking, staring. There were vibes of anxiety andconfusion in the air, and Aaron had created them. He felt like hehad super powers. The boy had even given him a cool name.

He made Darth Vader sounds as he paid for his fruit withexact change. He didn’t want to touch any of the filthy registermoney. When the cashier tried to hand him his receipt, hebacked away as though she’d shoved a scorpion in his face andgot the hell out of there, the surgical mask hiding Hospital Man’sfiendish grin.

*

Samantha heard a thump, then a car alarm—a really annoyingone that detonated the silence with a noise-parade of horn honks.

She had just gone back to bed to die in peace, and now somecob-roller’s polluting machine was denying her that modestconsolation. She mummified herself in her sheets and went to thewindow to scowl.

In the middle of the lot, a white Honda’s headlights wereflashing. It was Martha Haggerty’s car. Martha lived in 304 withher FIV-positive cat, Nuggles. She didn’t seem to have a job.From what Samantha could gauge, Martha either collectedmoney from the government in some capacity, or was the beneficiary of spousal support from a long-ago marriage. She hadthe mail carrier’s schedule down like clockwork, and would standoutside the lobby smoking cigarillos so she could catch himbefore he got to her mailbox. She spent all day in her slippers andhousecoat with rollers in her hair, then by night transformed intoa full-on cougar, prowling the local bars in skin-tight leopardprint jumpsuits complete with scuffed leather jacket, ho

opearrings, and poufy glam-rock hair. Samantha and Aaron referredto her car as the purr-mobile, though at the moment it soundedmore like a robot goose in distress.

She looked around the bedroom for something to chuck atits windshield, but all she had were crumpled balls of Kleenex andsome Swiffer pads.

Someone on the floor above opened their window andshouted, “Shut that fucking thing off!”

Mr. Böröcz came out into the lot and approached the vehicle.He stood with his hands on his hips, the bottom of his massive guthanging out of his barbecue sauce-stained T-shirt. He was staringat something feathery and crooked on the hood of the car.

Samantha pushed the curtains aside and pressed her foreheadagainst the windowpane. The crooked thing was a dead seagull.There were no trees hanging over the parking lot, no poles orelectrical wires. Judging by the size of the dent and the spatteringof blood and feathers, the bird must have fallen mid-flight andfrom quite a distance, like a down-coated cannon ball.

Zack Pike, the building’s resident burnout and marijuanadealer, opened his window across the lot. “What the fuck’s theproblem down there, yo?”

“This bird fall on Martha’s car,” Mr. Böröcz shouted.Samantha noticed that his Hungarian accent thickened likegoulash when he was angry or under stress. “She not in apartment.”

“Jesus fuck,” Zack Pike snarled.

The door to Ms. Fenster’s old unit opened, and out came theyoung man in black. It took Samantha a moment to realize thatthe spear-like tool in his hand was a re-shaped coat hanger. Hestood talking to Mr. Böröcz for a second, then carefully inserted the coat hanger into the small crack below the window on thedriver’s side door. Samantha watched his arms as he worked, andin a matter of seconds he’d managed to unlock it.

Mr. Böröcz clapped his hands together and did a little dance,his belly jiggling, as the man in black opened the door, stuck hisface down near the gas pedal, and began fiddling with whatSamantha imagined was a tangled knot of sizzling and verydangerous wires. There were two wing-shaped sweat stains onthe young man’s back. After only a minute of doing whatever hewas doing, the honking stopped.

Touching Strangers

Touching Strangers Poison Shy

Poison Shy